When is it Best to Bunt?

Photo Credit: Hannah Foslien/Getty Images

There have been many analyses over the years about the best situations to bunt. Tom Tango’s The Book: Playing the Percentages in Baseball has a thorough analysis of when a team should sacrifice bunt, considering factors such as the on-base percentage of the on-deck hitter and the speed of the batter, as well as the score, game state, and run scoring environment.

In this analysis I will take a look at the last two years of bunt attempts (4733 attempts, just under one bunt attempt per game) to assess which situations bunts have been most successful in improving an offense’s run scoring and improving an offense’s win probability. I’ll also assess the pitch characteristics of the pitches that bunts have been most and least successful against.

I define a bunt attempt as any time a batter bunts the ball in play, bunts the ball foul, or attempts to bunt and misses the ball. Pitches in which a batter squares to bunt and pulls back to take the pitch are not included. My analysis is focused on the last two years of bunting because that time period is after the National League adopted the designated hitter (DH). Before that, the National League run scoring environment was less prolific, with the pitchers batting and often bunting.

Over the last two years, bunting has added 9.9 wins to the bunting team, despite costing the bunting team 79 runs. This again explores the paradoxical tradeoff between scoring runs and winning games that I have discussed before with sacrifice flies. So how important is being able to bunt to your team? It’s worth about 0.165 wins per season.

Evaluating Bunting for Each Game State

From Figure 1 below, we see that bunting has been the most successful from a win probability standpoint in the following game states: when the bases are empty with 0 or 1 outs, first and second and 0 outs, first and third with 1 out, and man on second and 0 outs. Bunting has been the least successful with a man on first and 0 outs.

Figure 1: Win Probability Added (wpa) by bunting in each game state for the last two seasons

From Figure 2, we see that bunting has been the most successful from a run scoring standpoint when the bases are empty and 0 outs. Bunting has been least successful with first and second and 0 outs, man on first and 0 outs, and man on second with 0 outs.

Figure 2: Run Value added by bunting in each game state for the past two seasons

What do these result tell us regarding when the batter should bunt?

The best use of a bunt is, by far, to surprise the opponent and bunt for a single with 0 outs and the bases empty.

Don’t sacrifice bunt with a man on first and no outs! Tango says this is okay from a theory perspective, and perhaps it is in a low run scoring environment (playoff game) with a poor hitter at bat and a series of good hitters coming up next. But from a modern day bunt execution perspective, it is wasteful.

You can sacrifice bunt with a runner on second and 0 outs or runners on first and second with 0 outs. However, this must be done very late in the game, and preferably in a potential walkoff win situation, since you are sacrificing a lot of run expectancy to maximize the chance that you score exactly one run.

Evaluating Bunting based on Pitch Characteristics

Pitch Type

As evident from Figure 3, four-seam fastballs and sinkers are the easiest pitches to bunt. The “rising” fastball has been coined as the toughest pitch to bunt in the past, but the data may suggest otherwise.

The toughest pitches to bunt are sliders and sweepers. Against batters with the same handedness as the pitcher, the slider or sweeper can not only get the batter reaching for the ball due to the change of speed, but can also make the batter miss the ball due to the lateral movement away from him. Against batters of opposite handedness, sliders and sweepers can again get batters reaching with the change of speed, as well as potentially jam batters running in on their hands.

Figure 3: Win Probability Added (wpa) by bunting against each pitch type in the last two seasons. CH=Changeup, CU=Curveball, EP=Eephus Pitch, FC=Cutter, FF=4-seamer, FS=Splitter,KC=Knuckle Curve, SI=Sinker, SL=Slider, ST=Sweeper, SV=Slurve

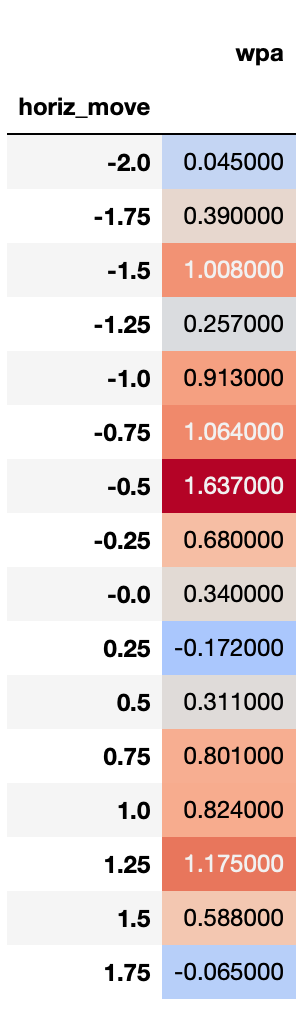

Horizontal Movement

Pitches with about 6 inches of induced horizontal break to the arm-side are the easiest to bunt, as evident from Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Win Probability Added (wpa) by bunting, grouped by induced horizontal break (ft), for the last two seasons

Vertical Movement

Pitches that have 16 inches of induced vertical rise are the easiest to bunt. However, as the rise creeps up beyond that level, bunting does become difficult. So the extreme rising fastball is indeed difficult to bunt, despite the typical rising fastball being very buntable. Pitches with 12 or more inches of vertical drop are difficult to bunt.

Figure 5: Win Probability Added (wpa) by bunting, grouped by induced vertical break (ft), for the last two seasons

Velocity

From a velocity point of view, 92 mph pitches are the easiest to bunt. Bunting is more difficult if the pitcher can throw 100 mph+ of if the pitcher is throwing in the 78 to 82 mph range.

Figure 6: Win Probability Added (wpa) by bunting, grouped by pitch velocity, for the last two seasons